Overview

1 Tourism and Waste

Barcelona waste production, Tourism Industry, Airbnb, QGIS, Open Souce Data, IAAC

2 Affordable Alternative Housing

Berlin Housing Models, Housing Associations, Cooperatives, Baugruppen, Mapbox, Tableau, OpenStreetMap, Open Source Data, Data Sourcing

Big Data Urbanism

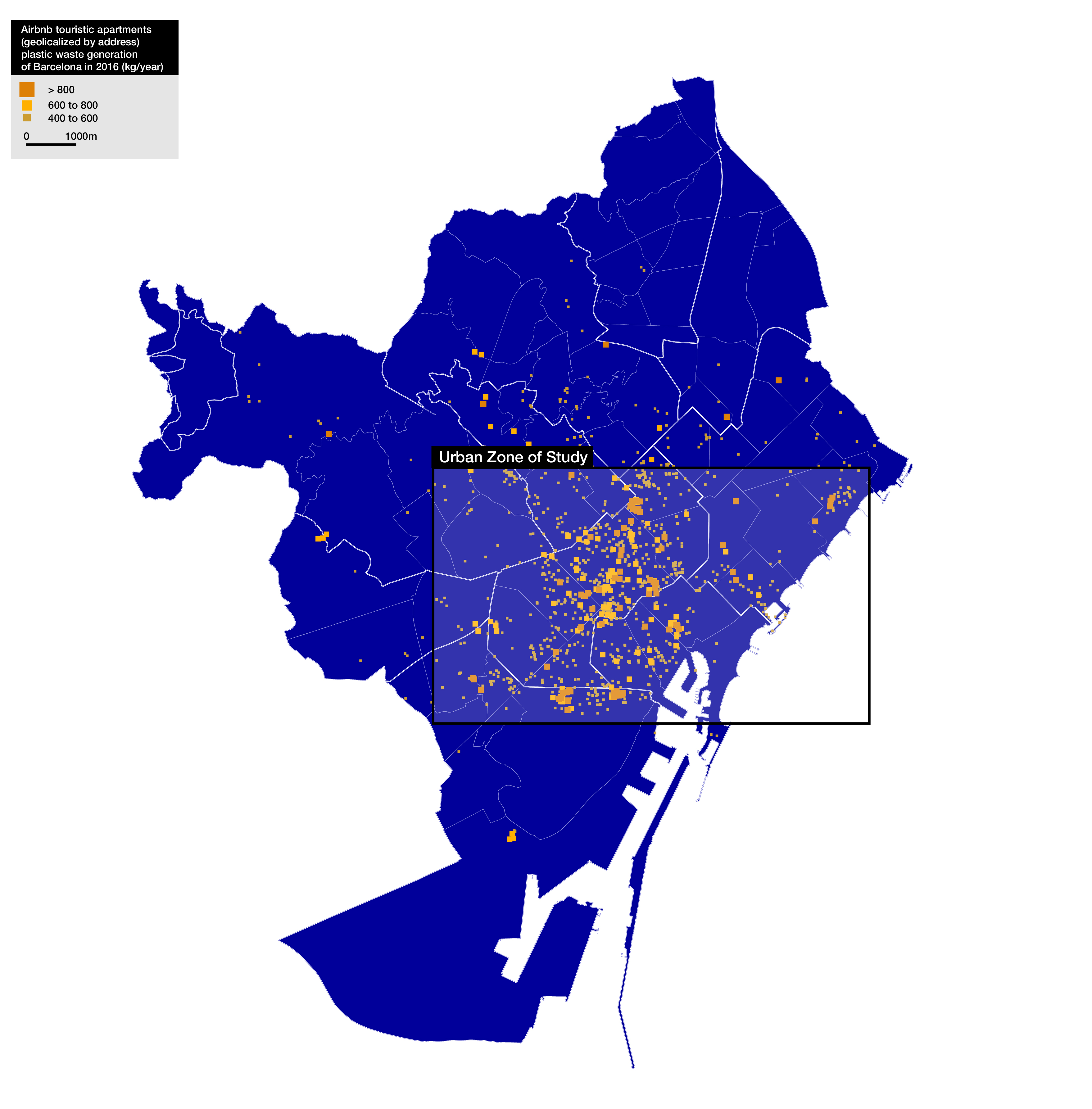

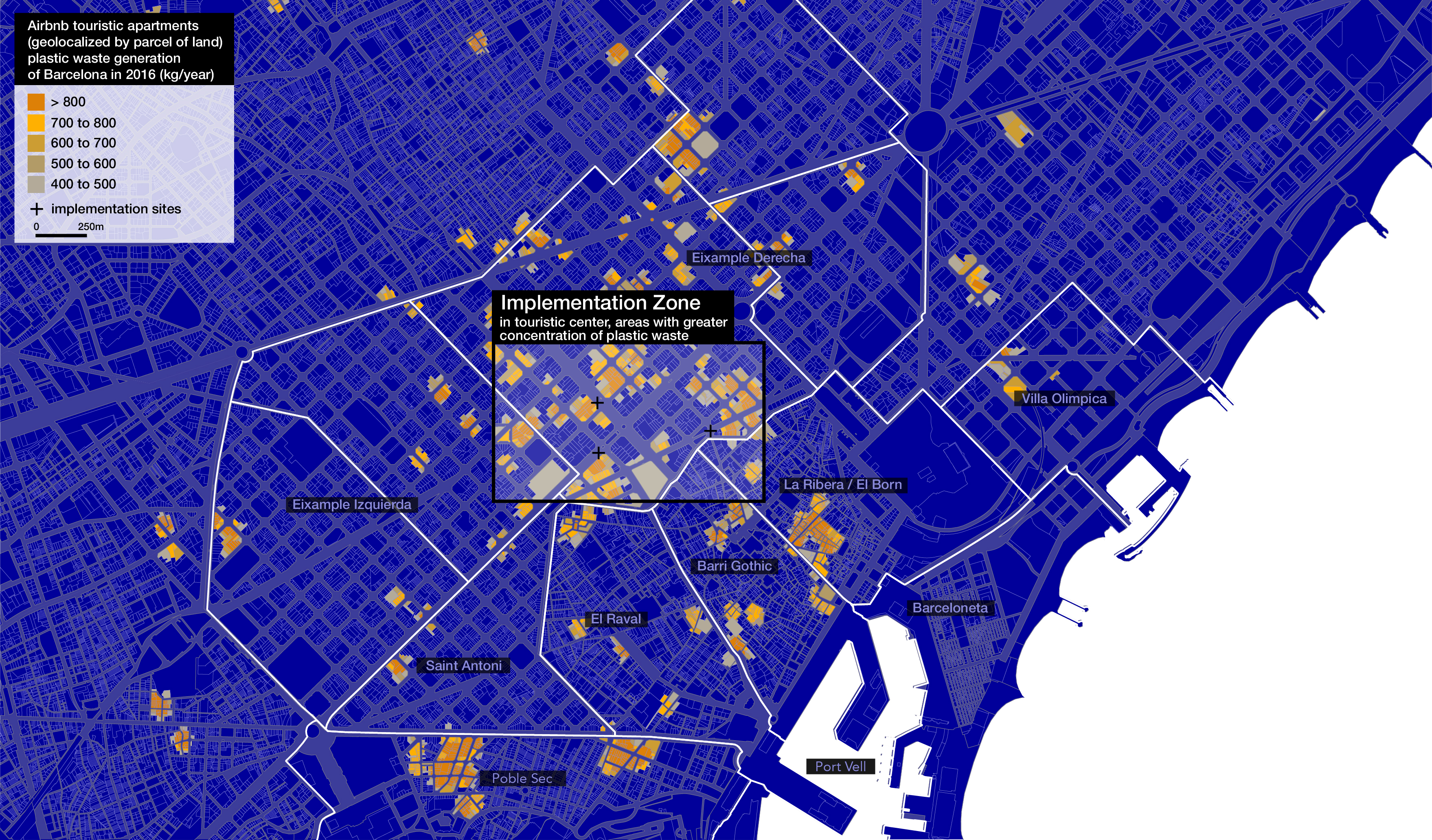

(Selected) Open Data Spatial MappingIn the current context, our cities are in need of more urban space of quality, where citizens can walk and enjoy outdoor activities with more space. Cars are slowly leaving the streets and giving space to new modes of transportation and more pedestrian spaces with examples such as the SuperBlock concept in Barcelona, or the recent modification for the COVID situation, especially needed in crowded space where tourism has increased those need for space.

On the other hand cities are producing a very large amount of trash and need to shift towards a more circular economy. Digital technologies including computational design, robotic fabrication and computer vision can allow us to rethink our production model and adapt them to the new requirements of circular economy.

Through the use of QGIS and Open Data, here explored is the relationship between touristic density, urban space requirements, and trash quantity — data analysis gathered during a workshop by IAAC, part of Digital Futures 2020

Issues of housing affordability affecting many major cities have led to a recent proliferation of alternative housing and development models. This is particularly notable in Berlin, where the State currently contributes and invests in various models as a measure to alleviate an increasingly unaffordable property market.

However, do these alternative ownership models cater well to those worst off in the market and low-income communities in threat of displacement? Or do they rather inform cheaper housing for the middle-class population and new-arrivals, potentially speeding gentrification?

Here, we explore these questions through urban data analysis. What emerges is a narrative of an array of alternative ownership models, each with their own unique characteristics, which in turn, coupled with market forces, dictate their distribution.

However, do these alternative ownership models cater well to those worst off in the market and low-income communities in threat of displacement? Or do they rather inform cheaper housing for the middle-class population and new-arrivals, potentially speeding gentrification?

Here, we explore these questions through urban data analysis. What emerges is a narrative of an array of alternative ownership models, each with their own unique characteristics, which in turn, coupled with market forces, dictate their distribution.